Shabbos: The Light We Preserve in Galus

Understanding Shabbos through the lens of Parashas Miketz

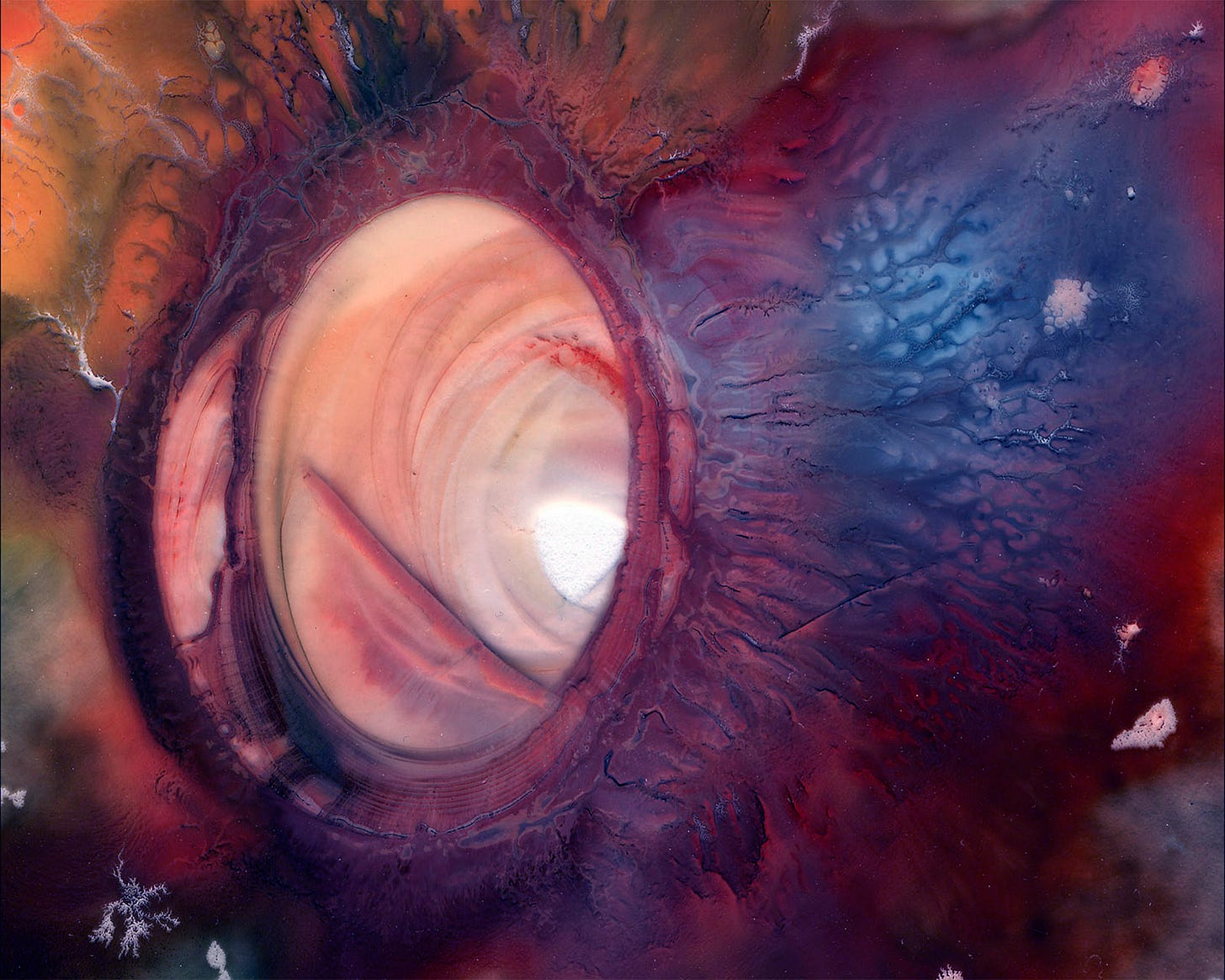

This has been a confusing week. On one hand, we saw darkness and hate in a way that rattled us to our very core. On the other hand, we have been lighting up our homes every night with Chanukah candles. We have been living a week of darkness and light. We have been living a week of reality. Reality keeps moving, and we keep moving with it, as hard as that may be.

This is the message of Parashas Miketz. Yosef shows how to preserve light inside darkness without romanticizing the darkness, while Shabbos shows that light can arrive from Above even when nothing down here feels ready for it.

Previously, we learned the idea that the segments of Yaakov’s life where he spent decades living with Lavan, needing to find the light in the darkness. Then he went back to Canaan, a place of light but beset with shadows and lingering darkness, setting a foundation for his children, primarily Yosef and Yehuda. As discussed, Yosef represents the light that survives the darkness, Yehuda represents the darkne…